Since I imagine a number of you will have different editions of this text, I'm providing chapter numbers below.

Friday March 19: Up to Chapter 10

I highly suggest that you try to finish the text over spring break.

Monday March 29: Up to Chapter 21

Wednesday March 31: Up to Chapter 27

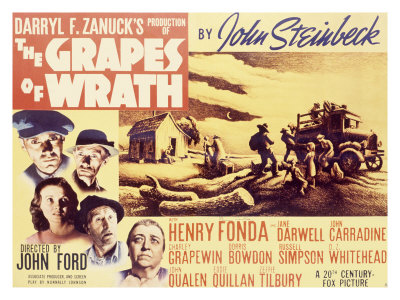

Friday April 2: To end; clips from John Ford's film will be shown in class.

This novel opens with a lot of description of the land and raises questions of land ownership. The owners of the land possess the legal rights to it, but the tenants live and work on the land. They have a relationship with the land; their bond runs deeper than a land title. The tenants say, “Grampa took up the land…and Pa was born here…it’s our land. We measured it and broke it up. We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours. That’s what makes it ours—being born on it, working it, dying on it. That makes ownership, not a paper with numbers on it” (Ch. 5) Refusing to leave the land, Muley gives up his family and his life to stay and roam aimlessly. Grandpa also refuses to leave. He says, “This country ain’t no good, but it’s my country.”

ReplyDeleteBy emphasizing the bonds the tenants have with the land, Steinbeck shows the courage the Joads (and thousands of others) exhibit in leaving their land for the unseen promise of California. It also shows the desperation of these people, who are willing to leave everything in order to find work and food.

I haven't got far enough into the reading yet (up to chapter 4) but I have really enjoyed it so far, so, I apologize now for this being a pretty short blog. The most noticeable thing about Steinbeck's style of writing in this book is the regional diction that the characters use. It is comparable to _As I Lay Dying_ in so much as I have to really think about what it is that these characters are saying. An example of this is "somepin" on page 10. Until I said it aloud, I was unclear that he meant "something."

ReplyDeleteAlso, Steinbeck seems to be very descriptive like Agee was in _Let Us Now Praise Famous Men_. Chapter 1 and it's description of the land and the dustbowl is really extensive, but it's much easier to follow than Agee's writing was. The book has been interesting so far, I'm excited to get further into it - I will admit that I'm one of those people that has never had to read it before.

I haven't gotten very far in the book either since I've been out of town, only to about chapter 5.

ReplyDeleteI think it's interesting how blatantly didactic Steinbeck is in this text. I've read Of Mice and Men, and it didn't have such blatant moral messages (aside from the "You don't let someone else shoot your own dog" thing...)

Naturally, I'm talking about Chapter 3, the Turtle Chapter. The first time I read the story in high school, I didn't understand the purpose of the turtle at all. I thought it was ridiculous and had no place in the story. However, since we've been studying modernist texts and different formatting choices of the authors, I feel much better about the turtle chapter. It reminds me a lot of Agee's "conversation in the lobby". It has nothing to do with the actual plot of the story; however, it basically sums up the novel as a whole. I also like how, instead of Steinbeck saying "There are two types of people in this world", he shows the types through this little side story. I think it's actually my favorite part thus far.

Sorry if this didn't make any sense, I've been in a car for the last seven hours or so. Forgive me. Next week I'll be coherent, I promise.

My favorite part of the assigned section was the description of the tractor and driver in chapter 5 (page 48 and 49 in my edition). The driver is like an automaton being controlled remotely by a larger entity, but is still entirely human, covered over in a faceless, skinless shell that betrays his humanity and disconnects him from his surroundings. The tractor is a monster with "twelve curved iron penes erected in the foundry, orgasms set by gears, raping methodically, raping without passion" (49). The driver pilots the creature but doesn't control it. I found this description to be very science fiction. It conjures up an image of something biomechanical, and reminds me of the artwork of HR Giger.

ReplyDeleteI'm really excited to get to re-read this book! I read it my junior year of High School and liked it alot! It's an easy to read book that shouldn't be too bad to read or get through over the break :)

ReplyDeleteI agree with Liz that the Turtle chapter (3) is a little confusing. but after you can re-read this book with a couple more years knowledge it. It does flow as James Agee's text bout the lobby scene did. Its almsot as if Steinbeck knows the readers are going to need a little bit of a pause from the text, but putting that chapter in the beginning of the novel seemed rather odd to me.

I look forward to completely re-reading this text!!!

Here's an interesting coincidence: as I started reading _Grapes_ for the very first time, I happened to be driving west on I-40, which follows almost the exact same route as Old Route 66. The weather was crazy going through Oklahoma (that big snowstorm was coming through), so we got a little taste of what the road must have been like for the Joads, crawling along at 30mph, trying to keep the car safe, with all our possessions piled up behind us. (Okay, not ALL our possessions, but enough for a week of camping). Without meaning to, we even made many of the same stops, including Henrietta and Santa Rosa. (By the way, you do NOT want your car to break down in Santa Rosa. It's desolate.) When we got to the desert, I imagined having to camp on the side of the road in that inhospitable country that seems to go on forever.

ReplyDeleteIt's hard for me to think of one thing that stands out to me about the novel. I mean, when I read for school, I try to read critically and all that, but Steinbeck just sucks me right in, and the story is so compelling that I have trouble maintaining a critical distance. I am interested, though, in the things that haven't changed since the 30's. We don't plant cotton in Oklahoma anymore, but we still farm one crop fence-to-fence, even though we've known for years how destructive monoculture is. I'm also struck by the way that the owners and company men justify their actions and attitudes. So much of what they say sounds a lot like our current debates over bank bailouts, immigration reform, and health care reform.

I'll try to get a little more objective by discussion-time, but for now, I

a.)love Ma

b.)want to go on strike

and c.) got the sperit.

I really like this book. It seems to have a little bit of everything: romance, violence, religion, labor- just about every quality a book could contain.

ReplyDeleteI loved Pa. He continually made me fall onto the ground in hysterics. I have this mental image of this little old man who runs around yelling profanity, refusing to be tamed by anyone. I was shocked and sad when he died but his death was significant and symbolizing his physical ties to the land. His death, although a disappointment, added to my connection with the book.

Like the other commenters, I am getting sucked into this book. I'm not sure what it is about Steinbeck's writing, but I noticed that the same thing happened to me when I read Of Mice and Men in high school. It's like I just start reading, and then I can't stop. When I come to myself, I've read for four hours straight without stopping.

ReplyDeleteOne thing I've noticed about The Grapes of Wrath that I really like is its overall structure. Steinbeck sets it up with alternating short and long chapters. The short chapters speak of the people in general - how they act, what they are doing. The longer chapters detail the actions of the Joads, and their trials along their journey. I think this structure works very well for a long epic novel like this. It creates a kind of rhythm, and the shorter chapters provide breaks when the narration about the Joads could become tedious. I know this isn't any kind of profound realization, but I think it is a perfect choice on Steinbeck's part, and it reflects his excellent skill of storytelling.

We hinted at Casy's character in class the other day, and I would like to further my observations of the worn down preacher. I feel like his thoughts and question about religion were very deep and still issues people struggle with today, Casey remembers how "the more grace a girl got in her, the quicker she wants to go out in the grass". This line made me laugh A. because its funny coming from a preacher and B. there is truth in what he is saying. I feel like a lot of time Christians fall back upon grace that covers all sins and so they feel free to do anything because they are covered by grace, I think this is still an issue Christians struggle with. ALso, this plays in with the idea that when your feeling the spirit, it might even invoke a more passionate desire for other things...such as sex or to feel which we saw a lot in God's Little Acre. Casy plays with the idea that people are filled with the spirit but also still sinning which is also a truth seen in the Church. Casy takes all these things he sees and comes up with a philosophy which is very sacrilegious: saying that "maybe its all men an all women we love; maybe that's the holy spirit-the human sperit-the whole shebang. Maybe all men got one big soul everybody's a part of." Casy seems to be making his own religious ideas up in order to compensate for his own sins or make it into not being sins, since the holy spirit is the human spirit that loves one another. I think it would be fun to go over this passage in class...cause i don't really understand it but i want to and it seems interesting : ) Also, the idea of imagining Load pulling a girls pigtail in the water while being baptized is pretty historical...just a side note.

ReplyDeleteCasey kind of reminds me of Hazel Motes from O'Connor's Wise Blood, though certainly not in character (Casey is a lot more easy going and a lot more, well, likable). Both characters are men that have claim to have cast off all sacrament, but still remain deeply spiritual, even if they don't want to admit it. Casey is a willing but unwilling spiritual figurehead. His Christ-like qualities are made evident later in the book (won't spoil that here, since I don't think we're technically there in the assigned reading). He's a contradicting and compelling character. I like him.

ReplyDeleteIn his book _Faulkner and the Great Depression_, Ted Atkinson makes an interesting comparison between the Bundrens and the tenants heading to California in _The Grapes of Wrath_, claiming that they are similar in their determined effort to preserve their dignity. While this may seem at first to be a bold claim considering the Bundren’s ridiculous journey, which was far from dignified, Atkinson’s point is that both the Bundrens and the tenants try to maintain a sense of self-reliance as they move from independence to dependence. Just as Anse refuses Samson’s offer for dinner and repeatedly declares his desire to not be beholden to others, the tenants refuse handouts. Jessie (a woman on the Ladies Committee) is outraged when Mrs. Joyce tells her she won’t accept charity. Jessie rages, “They ain’t no charity in this here camp. We won’t have no charity” (315). When they do accept assistance, they do so only with the illusion that they are not receiving help. Anse receives help numerous times along his journey but either does not acknowledge it or places the debt on Addie. The man who buys bread in the diner scene in The Grapes of Wrath accepts the loaf and the candy at a reduced price but does not acknowledge the waitress’s charity. In America, a country in which people pride themselves on their self-reliance, the proud but desperate poor found themselves forced to accept help. By the end of the novel though, it is not self-reliance but mutual help that offers hope.

ReplyDeleteBlogspot was being mean last night and wouldn't let me post, so this is a little late.

ReplyDeleteI'm finding that I enjoy this book much more now, reading it in college, than I did in high school. I especially like the interculary (sp?) chapters that seem to be social commentary essays. They could, in my opinion, completely be taken out of the book and published today as essays on the economic condition.

That being said, I think part of the reason I enjoy this so much now is that I can see clear parallels to today's society. The tenant farmers being kicked off of their land echoes the idea of so many people being kicked out of their homes due to foreclosure in today's economy. Except now, there's no dreamy California to go to. I'm curious if, had there been a whole new frontier discovered say, last year, how many people in the low-income areas would be packing up and moving. I'm willing to bet it would be quite similar to the Dust Bowl migration.

Incidentally, I'm also curious as to what Ma would think about the health care reform...

I love Ma Joad. She is the essence of my late grandmother. In the beginning of the text, there are indirect implications of the female role in this life. They discuss things such as who gets to sit in the cab of the truck, and we see who is cooking and cleaning. But as the book progresses, we see a whole new side to Ma Joad. She turns into the dominant family figure, eventually taking Pa's place in the family structure.

ReplyDeleteThis begins when we see Ma getting a tire iron out of the car in order to defend her decision for the family to stay together rather than split up. The men say she is being "sassy." When I read that I nearly laughed out loud. Towards the end, her attitude is nearly the opposite as in the beginning, and she takes a stand. In chapter 26 Pa was threatening to get a stick after Ma, because of her calling all the shots. She said, "But you jus' get you a stick now an' you ain't lickin' no woman; you're a-fightin', 'cause I got a stick all laid out too." This clearly indicates the necessity of everyone's input to the predicament they were in, as before, only the men would huddle in the circles and work things out. Now Ma was putting her two cents in, and she was defending her right to do so no matter what it would cost her. Steinbeck was most likely nodding to the struggles in society for women's rights throughout the history of America.